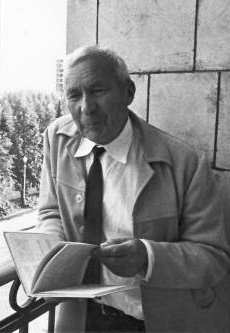

Andrey Kolmogorov (nonfiction)

Andrey Nikolaevich Kolmogorov (Russian: Андрей Николаевич Колмогоров; IPA: [ɐnˈdrʲej nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ kəlmɐˈɡorəf], 25 April 1903 – 20 October 1987) was a 20th-century Soviet mathematician who made significant contributions to the mathematics of probability theory, topology, intuitionistic logic, turbulence, classical mechanics, algorithmic information theory, and computational complexity.

Andrey Kolmogorov was educated in his aunt Vera's village school, and his earliest literary efforts and mathematical papers were printed in the school journal "The Swallow of Spring". Andrey (at the age of five) was the "editor" of the mathematical section of this journal. Kolmogorov's first mathematical discovery was published in this journal: at the age of five he noticed the regularity in the sum of the series of odd numbers:

1=1^2; 1+3=2^2; 1+3+5=3^2,1=1^2; 1+3=2^2; 1+3+5=3^2, etc.

In 1910, his aunt adopted him, and they moved to Moscow, where he graduated from high school in 1920. Later that same year, Kolmogorov began to study at the Moscow State University and at the same time Mendeleev Moscow Institute of Chemistry and Technology. Kolmogorov writes about this time:

I arrived at Moscow University with a fair knowledge of mathematics. I knew in particular the beginning of set theory. I studied many questions in articles in the Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron, filling out for myself what was presented too concisely in these articles.

Kolmogorov gained a reputation for his wide-ranging erudition. While an undergraduate student in college, he attended the seminars of the Russian historian S. V. Bachrushin, and he published his first research paper on the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries' landholding practices in the Novgorod Republic. During the same period (1921–22), Kolmogorov worked out and proved several results in set theory and in the theory of Fourier series.

In 1922, Kolmogorov gained international recognition for constructing a Fourier series that diverges almost everywhere. Around this time, he decided to devote his life to mathematics.

In 1925, Kolmogorov graduated from the Moscow State University and began to study under the supervision of Nikolai Luzin. He formed a lifelong close friendship with Pavel Alexandrov, a fellow student of Luzin; indeed several authors have claimed that the two friends were involved in a homosexual relationship.

Kolmogorov (together with Aleksandr Khinchin) became interested in probability theory. Also in 1925, he published his work in intuitionistic logic — On the principle of the excluded middle, in which he proved that under a certain interpretation, all statements of classical formal logic can be formulated as those of intuitionistic logic. In 1929, Kolmogorov earned his Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree, from Moscow State University.

In 1930, Kolmogorov went on his first long trip abroad, traveling to Göttingen and Munich, and then to Paris. He had various scientific contacts in Göttingen. First of all with Courant and his students working on limit theorems, where diffusion processes turned out to be the limits of discrete random processes, then with Hermann Weyl in intuitionistic logic, and lastly with Edmund Landau in function theory. His pioneering work, About the Analytical Methods of Probability Theory, was published (in German) in 1931. Also in 1931, he became a professor at the Moscow State University.

In 1933, Kolmogorov published his book, Foundations of the Theory of Probability, laying the modern axiomatic foundations of probability theory and establishing his reputation as the world's leading expert in this field. In 1935, Kolmogorov became the first chairman of the department of probability theory at the Moscow State University. Around the same years (1936) Kolmogorov contributed to the field of ecology and generalized the Lotka–Volterra model of predator-prey systems.

In 1936, Kolmogorov and Alexandrov were involved in the political persecution of their common teacher Nikolai Luzin, in the so-called Luzin affair.

In a 1938 paper, Kolmogorov "established the basic theorems for smoothing and predicting stationary stochastic processes"—a paper that had major military applications during the Cold War. In 1939, he was elected a full member (academician) of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

During World War II Kolmogorov contributed to the Russian war effort by applying statistical theory to artillery fire, developing a scheme of stochastic distribution of barrage balloons intended to help protect Moscow from German bombers.

In his study of stochastic processes, especially Markov processes, Kolmogorov and the British mathematician Sydney Chapman independently developed the pivotal set of equations in the field, which have been given the name of the Chapman–Kolmogorov equations.

Later, Kolmogorov focused his research on turbulence, where his publications (beginning in 1941) significantly influenced the field. In classical mechanics, he is best known for the Kolmogorov–Arnold–Moser theorem, first presented in 1954 at the International Congress of Mathematicians. In 1957, working jointly with his student V. I. Arnold, he solved a particular interpretation of Hilbert's thirteenth problem. Around this time he also began to develop, and was considered a founder of, algorithmic complexity theory – often referred to as Kolmogorov complexity theory.

Kolmogorov married Anna Dmitrievna Egorova in 1942.

He pursued a vigorous teaching routine throughout his life, not only at the university level but also with younger children, as he was actively involved in developing a pedagogy for gifted children (in literature, music, and mathematics).

At the Moscow State University, Kolmogorov occupied different positions, including the heads of several departments: probability, statistics, and random processes; mathematical logic. He also served as the Dean of the Moscow State University Department of Mechanics and Mathematics.

In 1971, Kolmogorov joined an oceanographic expedition aboard the research vessel Dmitri Mendeleev. He wrote a number of articles for the Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

In his later years, he devoted much of his effort to the mathematical and philosophical relationship between probability theory in abstract and applied areas.

Kolmogorov died in Moscow in 1987, and his remains were buried in the Novodevichy cemetery.

A quotation attributed to Kolmogorov is [translated into English]: "Every mathematician believes that he is ahead of the others. The reason none state this belief in public is because they are intelligent people."

Vladimir Arnold once said: "Kolmogorov – Poincaré – Gauss – Euler – Newton, are only five lives separating us from the source of our science".

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

- Algorithmic information theory (nonfiction) - the study of the irreducible information content of strings (or other data structures). Because most mathematical objects can be described in terms of strings, or as the limit of a sequence of strings, it can be used to study a wide variety of mathematical objects, including integers.

- Sydney Chapman (nonfiction)

- Leonhard Euler (nonfiction)

- Fourier series (nonfiction)

- Carl Friedrich Gauss (nonfiction)

- Kolmogorov complexity (nonfiction) - In algorithmic information theory, the Kolmogorov complexity of an object, such as a piece of text, is the length of the shortest computer program (in a predetermined programming language) that produces the object as output. It is a measure of the computational resources needed to specify the object. It is also known as algorithmic complexity, Solomonoff–Kolmogorov–Chaitin complexity, program-size complexity, descriptive complexity, or algorithmic entropy. Kolmogorov first published on the subject in 1963. The notion of Kolmogorov complexity can be used to state and prove impossibility results akin to Cantor's diagonal argument, Gödel's incompleteness theorem, and Turing's halting problem. In particular, for almost all objects, it is not possible to compute even a lower bound for its Kolmogorov complexity, let alone its exact value.

- Edmund Landau (nonfiction)

- Nikolai Luzin (nonfiction)

- Mathematician (nonfiction)

- Isaac Newton (nonfiction)

- Henri Poincaré (nonfiction)

- Set theory (nonfiction)

Doctoral students:

- Vladimir Arnold (nonfiction)

- Sergei N. Artemov (nonfiction)

- Grigory Barenblatt (nonfiction)

- Roland Dobrushin (nonfiction)

- Eugene Dynkin (nonfiction)

- Israil Gelfand (nonfiction)

- Boris Gnedenko (nonfiction)

- Leonid Levin (nonfiction)

- Per Martin-Löf (nonfiction)

- Andrei Monin (nonfiction)

- Sergey Nikolsky (nonfiction)

- Alexander Obukhov (nonfiction)

- Yuri Prokhorov (nonfiction)

- Yakov Sinai (nonfiction)

- Albert Shiryaev (nonfiction)

- Anatoli Vitushkin (nonfiction)

- Vladimir Uspensky (nonfiction)

- Akiva Yaglom (nonfiction)

External links:

- Andrey Kolmogorov @ Wikipedia