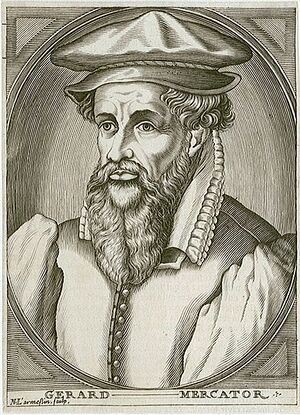

Gerardus Mercator (nonfiction)

Gerardus Mercator (/dʒɪˈrɑːrdəs mɜːrˈkeɪtər/; 5 March 1512 – 2 December 1594) was a 16th-century geographer, cosmographer, and cartographer from Flanders. He is most renowned for creating the 1569 world map based on a new projection which represented sailing courses of constant bearing (rhumb lines) as straight lines—an innovation that is still employed in nautical charts.

Mercator was one of the pioneers of cartography and is widely considered the most notable figure of the school in its golden age (approximately 1570s–1670s). In his own day, he was a notable as maker of globes and scientific instruments. In addition, he had interests in theology, philosophy, history, mathematics and geomagnetism. He was also an accomplished engraver and calligrapher. Unlike other great scholars of the age he travelled little and his knowledge of geography came from his library of over one thousand books and maps, from his visitors and from his vast correspondence (in six languages) with other scholars, statesmen, travellers, merchants and seamen. Mercator's early maps were in large formats suitable for wall mounting but in the second half of his life, he produced over 100 new regional maps in a smaller format suitable for binding into his Atlas of 1595. This was the first appearance of the word Atlas in reference to a book of maps. However, Mercator used it as a neologism for a treatise (Cosmologia) on the creation, history and description of the universe, not simply a collection of maps. He chose the word as a commemoration of the Titan Atlas, "King of Mauretania", whom he considered to be the first great geographer.

A large part of Mercator's income came from sales of his terrestrial and celestial globes. For sixty years they were considered the finest in the world, and were sold in such great numbers that there are many surviving examples. This was a substantial enterprise involving the manufacture of the spheres, printing the gores, building substantial stands, packing and distributing all over Europe. He was also renowned for his scientific instruments, particularly his astrolabes and astronomical rings used to study the geometry of astronomy and astrology.

Mercator wrote on geography, philosophy, chronology and theology. All of the wall maps were engraved with copious text on the region concerned. As an example the famous world map of 1569 is inscribed with over five thousand words in fifteen legends. The 1595 Atlas has about 120 pages of maps and illustrated title pages but a greater number of pages are devoted to his account of the creation of the universe and descriptions of all the countries portrayed. His table of chronology ran to some 400 pages fixing the dates (from the time of creation) of earthly dynasties, major political and military events, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and eclipses. He also wrote on the gospels and the old testament.

Mercator was a devout Christian born into a Catholic family at a time when Martin Luther's Protestantism was gaining ground. He never declared himself as a Lutheran but he was clearly sympathetic and he was accused of heresy by Catholic authorities; after six months in prison he was released unscathed. This period of persecution is probably the major factor in his move from Catholic Leuven (Louvain) to a more tolerant Duisburg, in the Holy Roman Empire, where he lived for the last thirty years of his life. Walter Ghim, Mercator's friend and first biographer, describes him as sober in his behaviour, yet cheerful and witty in company, and never more happy than in debate with other scholars. Above all he was pious and studious until his dying days.

Mercator's life

= Early years

Gerardus Mercator was born Geert or Gerard (de) Kremer (or Cremer), the seventh child of Hubert (de) Kremer and his wife Emerance in Rupelmonde, Flanders, a small village to the southwest of Antwerp, all of which lied in the fiefdom of Habsburg Netherlands. His parents came from Gangelt in the Holy Roman Duchy of Jülich (present-day Germany). At the time of the birth they were visiting Hubert's brother (or uncle[6]) Gisbert de Kremer.[7] Hubert was a poor artisan, a shoemaker by trade, but Gisbert, a priest, was a man of some importance in the community. Their stay in Rupelmonde was brief and within six months they returned to Gangelt and there Mercator spent his earliest childhood until the age of six.[8] In 1518, the Kremer family moved back to Rupelmonde,[9] possibly motivated by the deteriorating conditions in Gangelt—famine, plague and lawlessness.[10] Mercator would have attended the local school in Rupelmonde from the age of seven, when he arrived from Gangelt, and there he would have been taught the basics of reading, writing, arithmetic and Latin.

Macropedius

After Hubert's death in 1526, Gisbert became Mercator's guardian. Hoping that Mercator might follow him into the priesthood, he sent the 15-year-old Geert to the famous school of the Brethren of the Common Life at 's-Hertogenbosch[12] in the Duchy of Brabant. The Brotherhood and the school had been founded by the charismatic Geert Groote who placed great emphasis on study of the Bible and, at the same time, expressed disapproval of the dogmas of the church, both facets of the new "heresies" of Martin Luther propounded only a few years earlier in 1517. Mercator would follow similar precepts later in life—with problematic outcomes.

During his time at the school the headmaster was Georgius Macropedius, and under his guidance Geert would study the Bible, the trivium (Latin, logic and rhetoric) and classics such as the philosophy of Aristotle, the natural history of Pliny and the geography of Ptolemy.[13] All teaching at the school was in Latin and he would read, write and converse in Latin—and give himself a new Latin name, Gerardus Mercator Rupelmundanus, Mercator being the Latin translation of Kremer, which means "merchant". The Brethren were renowned for their scriptorium[14] and here Mercator might have encountered the italic script which he employed in his later work. The brethren were also renowned for their thoroughness and discipline, well attested by Erasmus who had attended the school forty years before Mercator.[15]

= University of Leuven 1530–1532

From a famous school, Mercator moved to the famous University of Leuven, where his full Latin name appears in the matriculation records for 1530.[16] He lived in one of the teaching colleges, the Castle College, and, although he was classified as a pauper, he rubbed shoulders with richer students, amongst whom were the anatomist Andreas Vesalius, the statesman Antoine Perrenot, and the theologian George Cassander, all destined to fame and all lifelong friends of Mercator.

The general first degree (for Magister) centred on the teaching of philosophy, theology and Greek under the conservative Scholasticism which gave prime place to the authority of Aristotle.[17] Although the trivium was now augmented by the quadrivium[18] (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music), their coverage was neglected in comparison with theology and philosophy and consequently Mercator would have to resort to further study of the first three subjects in years to come. Mercator graduated Magister in 1532.

Antwerp 1532–1534

The normal progress for an able Magister was to go on to further study in one of the four faculties at Leuven: Theology, Medicine, Canon Law and Roman Law. Gisbert might have hoped that Mercator would go further in theology and train for the priesthood but Mercator did not: like many twenty year old young men he was having his first serious doubts. The problem was the contradiction between the authority of Aristotle and his own biblical study and scientific observations, particularly in relation to the creation and description of the world. Such doubt was heresy at the University and it is quite possible that he had already said enough in classroom disputations to come to the notice of the authorities:[20] fortunately he did not put his sentiments into print. He left Leuven for Antwerp,[21] there to devote his time to contemplation of philosophy. This period of his life is clouded in uncertainty.[22] He certainly read widely but only succeeded in uncovering more contradictions between the world of the Bible and the world of geography, a hiatus which would occupy him for the rest of his life.[23] He certainly could not effect a reconciliation between his studies and the world of Aristotle.

During this period Mercator was in contact with the Franciscan friar Monachus who lived in the monastery of Mechelen.[24] He was a controversial figure who, from time to time, was in conflict with the church authorities because of his humanist outlook and his break from Aristotelian views of the world: his own views of geography were based on investigation and observation. Mercator must have been impressed by Monachus, his map collection and the famous globe that he had prepared for Jean Carondelet, the principal advisor of Charles V.[25] The globe was constructed by the Leuven goldsmith Gaspar van der Heyden (Gaspar a Myrica c. 1496–c. 1549) with whom Mercator would be apprenticed. These encounters may well have provided the stimulus to put aside his problems with theology and commit himself to geography. Later he would say, "Since my youth, geography has been for me the primary subject of study. I liked not only the description of the Earth but the structure of the whole machinery of the world."

Gemma Frisius

Towards the end of 1534, the twenty-two-year-old Mercator arrived back in Leuven and threw himself into the study of geography, mathematics and astronomy under the guidance of Gemma Frisius.[27] Mercator was completely out of his depth but, with the help and friendship of Gemma, who was only four years older, he succeeded in mastering the elements of mathematics within two years and the university granted him permission to tutor private students. Gemma had designed some of the mathematical instruments used in these studies and Mercator soon become adept in the skills of their manufacture: practical skills of working in brass, mathematical skills for calculation of scales and engraving skills to produce the finished work.

Gemma and Gaspar Van der Heyden had completed a terrestrial globe in 1529 but by 1535 they were planning a new globe embodying the latest geographical discoveries.[29] The gores were to be engraved on copper, instead of wood, and the text was to be in an elegant italic script instead of the heavy Roman lettering of the early globes. The globe was a combined effort: Gemma researched the content, Van der Heyden engraved the geography and Mercator engraved the text, including the cartouche which exhibited his own name in public for the first time. The globe was finished in 1536 and its celestial counterpart appeared one year later. These widely admired globes were costly and their wide sales provided Mercator an income which, together with that from mathematical instruments and from teaching, allowed him to marry and establish a home. His marriage to Barbara Schellekens was in September 1536 and Arnold, the first of their six children, was born a year later.

The arrival of Mercator on the cartographic scene would have been noted by the cognoscenti who purchased Gemma's globe—the professors, rich merchants, prelates, aristocrats and courtiers of the emperor Charles V at nearby Brussels. The commissions and patronage of such wealthy individuals would provide an important source of income throughout his life. His connection with this world of privilege was facilitated by his fellow student Antoine Perrenot, soon to be appointed Bishop of Arras, and Antoine's father, Nicholas Perrenot, the Chancellor of Charles V.

Working alongside Gemma whilst they were producing the globes, Mercator would have witnessed the process of progressing geography: obtaining previous maps, comparing and collating their content, studying geographical texts and seeking new information from correspondents, merchants, pilgrims, travellers and seamen. He put his newly learned talents to work in a burst of productivity. In 1537, aged only 25, he established his reputation with a map of the Holy Land which was researched, engraved, printed and partly published by himself.

A year later, in 1538, he produced his first map of the world, usually referred to as Orbis Imago. In 1539/40 he made a map of Flanders and in 1541 a terrestrial globe. All four works were received with acclaim[33] and they sold in large numbers. The dedications of three of these works witness Mercator's access to influential patrons: the Holy Land was dedicated to Franciscus van Cranevelt who sat on the Great Council of Mechelen, the map of Flanders was dedicated to the Emperor himself and the globe was dedicated to Nicholas Perrenot, the emperor's chief advisor. The dedicatee of the world map was more surprising: Johannes Drosius, a fellow student who, as an unorthodox priest, may well have been suspected of Lutheran heresy.[34] Given that the symbolism of the Orbis Imago map also reflected a Lutheran view point, Mercator was exposing himself to criticism by the hardline theologians of Leuven.

In between these works he found time to write Literarum latinarum, a small instruction manual on the italic script.[36] The italic script (or chancery cursive) reached the Low Countries from Italy at the beginning of the sixteenth century and it is recorded as a form of typescript in Leuven in 1522.[37] It was much favoured by humanist scholars who enjoyed its elegance and clarity as well as the rapid fluency that could be attained with practice, but it was not employed for formal purposes such as globes, maps and scientific instruments (which typically used Roman capitals or gothic script). Mercator first applied the italic script to the globe of Gemma Frisius and thereafter to all his works, with ever-increasing elegance. The title page of this work is an illustration of the decorative style he developed.

In 1542, the thirty-year-old must have been feeling confident about his future prospects when he suffered two major interruptions to his life. First, Leuven was besieged by the troops of the Duke of Cleves, a Lutheran sympathiser who, with French support, was set on exploiting unrest in the Low Countries to his own ends.[39] This was the same Duke to whom Mercator turned ten years later. The siege was lifted but the financial losses to the town and its traders, including Mercator, were great. The second interruption was potentially deadly: the Inquisition called.

Persecution, 1543

At no time in his life did Mercator claim to be a Lutheran but there are many hints that he had sympathies in that direction. As a child, called Geert, he was surrounded by adults who were possibly followers of Geert Groote, who placed meditation, contemplation and biblical study over ritual and liturgy—and who also founded the school of the Brethren of the Common Life at 's-Hertogenbosch. As an adult Mercator had family connections to Molanus, a religious reformer who would later have to flee Leuven. Also he was a close friend and correspondent of Philip Melanchthon, one of the principal Lutheran reformers.[41] Study of the Bible was something that was central to Mercator's life and it was the cause of the early philosophical doubts that caused him so much trouble during his student days, doubts which some of his teachers would have considered to be tantamount to heresy. His visits to the free thinking Franciscans in Mechelen may have attracted the attention of the theologians at the university, amongst whom were two senior figures of the Inquisition, Jacobus Latomus and Ruard Tapper. The words of the latter on the death of heretics convey the atmosphere of that time:

It is no great matter whether those that die on this account be guilty or innocent, provided we terrify the people by these examples; which generally succeeds best, when persons eminent for learning, riches, nobility or high stations, are thus sacrificed.

It may well have been these Inquisitors who, in 1543, decided that Mercator was eminent enough to be sacrificed.[44] His name appeared on a list of 52 Lutheran heretics which included an architect, a sculptor, a former rector of the university, a monk, three priests and many others. All were arrested except Mercator who had left Leuven for Rupelmonde on business concerning the estate of his recently deceased uncle Gisbert. That made matters worse for he was now classified as a fugitive who, by fleeing arrest, had proved his own guilt.

Mercator was apprehended in Rupelmonde and imprisoned in the castle. He was accused of suspicious correspondence with the Franciscan friars in Mechelen but no incriminating writings were uncovered in his home or at the friary in Mechelen. At the same time his well placed friends petitioned on his behalf,[46] but whether his friend Antoine Perrenot was helpful is unknown: Perrenot, as a bishop, would have to support the activities of the Inquisition. After seven months Mercator was released for lack of evidence against him but others on the list suffered torture and execution: two men were burnt at the stake, another was beheaded and two women were entombed alive.[40]

Leuven 1543–1552

Mercator never committed any of his prison experiences to paper; all he would say was that he had suffered an "unjust persecution". For the rest of his time in Leuven his religious thoughts were kept to himself and he turned back to his work. His brush with the Inquisition did not affect his relationship with the court and Nicholas Perrenot recommended him to the emperor as a maker of superb instruments. The outcome was an Imperial order for globes, compasses, astrolabe and astronomical rings.[48] They were ready in 1545 and the Emperor granted the royal seal of approval to his workshop. Sadly they were soon destroyed in the course of the Emperor's military ventures and Mercator had to construct a second set, now lost.[49] He also returned to his work on a large up-to-date and highly detailed wall map of Europe[47] which was, he had already claimed on his 1538 world map, very well advanced. It proved to be a vast task and he, perfectionist that he was, seemed unable to cut short his ever-expanding researches and publish: as a result it was to be another ten years before the map appeared.

In 1547 Mercator was visited by the young (nineteen year old) John Dee who, on completion of his undergraduate studies in Cambridge (1547), "went beyond the seas to speak and confer with some learned men".[50] Dee and Mercator were both passionately interested in the same topics and they quickly established a close rapport which lasted throughout their lives. In 1548 Dee returned to Leuven (Louvain in Dee's text) and registered as a student: for three years he was constantly in Mercator's company.[51] Apart from a possible short visit to Duisberg in 1562[52] the two men did not meet but they corresponded frequently and by good fortune a number of their letters are preserved.[53] Dee took maps, globes and astronomical instruments back to England and in return furnished Mercator with the latest English texts and new geographical knowledge arising from the English explorations of the world. Forty years later they were still co-operating, Dee using Mercator's maps to convince the English court to finance Martin Frobisher's expeditions and Mercator still avidly seeking information of new territories.

The final success in Leuven was the 1551 celestial globe, the partner of his terrestrial globe of 1541. The records of the Plantin Press show that several hundred[54] pairs of globes were sold before the end of the century despite their high price—in 1570 they sold at 25 carolus guilders for a pair, equivalent to 2,500 euro in modern currency.[55] Celestial globes were a necessary adjunct to the intellectual life of rich patrons[56] and academics alike, for both astronomical and astrological studies, two subjects which were strongly entwined in the sixteenth century. Twenty-two pairs are still in existence.

Duisburg 1552–1594

In 1552 Mercator moved from Leuven to Duisburg in the Duchy of Cleves. He never gave his reasons for the move but several factors may have been involved: not having been born in Brabant he could never be a full citizen of Leuven; Catholic intolerance of religious dissidents in the Low Countries was becoming ever more aggressive and a man suspected of heresy once would never be trusted; the Erasmian constitution and the religious tolerance of Cleves must have appeared attractive; there was to be a new university in Duisburg and teachers would be required.[57] He was not alone; over the years to come many more would flee from the oppressive Catholicism of Brabant and Flanders to tolerant cities such as Duisburg.

The peaceful town of Duisburg, untroubled by political and religious unrest, was the perfect place for the flowering of his talent. Mercator quickly established himself as a man of standing in the town: an intellectual of note, a publisher of maps, and a maker of instruments and globes.[59] Mercator never accepted the privileges and voting rights of a burgher for they came with military responsibilities which conflicted with his pacifist and neutral stance. Nevertheless, he was on good terms with the wealthier citizens and a close friend of Walter Ghim, the twelve times mayor and Mercator's future biographer.[60]

Mercator was welcomed by Duke Wilhelm who appointed him as court cosmographer. There is no precise definition of this term other than that it certainly comprehends the disciplines of geography and astronomy but at that time it would also include astrology and chronology (as a history of the world from the creation). All of these were among Mercator's accomplishments but his patron's first call on his services was as a mundane surveyor of the disputed boundary between the Duke's territory of the County of Mark and the Duchy of Westphalia.

Around this time Mercator also received and executed a very special order for the Holy Roman Emperor a pair of small globes, the inner ("fist-size") Earth was made of wood and the outer celestial sphere was made of blown crystal glass engraved with diamond and inlaid with gold.[62] He presented them to the Emperor in Brussels who awarded him the title Imperatoris domesticus (a member of the Imperial household). The globes are lost but Mercator describes them in a letter to Philip Melanchthon[63] in which he declares that the globes were rotated on the top of an astronomical clock made for Charles V by Juanelo Turriano (Janellus).[64] The clock was provided with eight dials which showed the positions of the moon, stars and planets. The illustration shows a similar clock made by the German craftsman Baldewein at roughly the same time.

Mercator's theory of magnetism

Earlier, Mercator had also presented Charles V with an important pamphlet on the use of globes and instruments and his latest ideas on magnetism: Declaratio insigniorum utilitatum quae sunt in globo terrestri : coelesti, et annulo astronomico (A description of the most important applications of the terrestrial and celestial globes and the astronomical ring).[65] The first section is prefaced by Mercator's ideas on magnetism, the central thesis being that magnetic compasses are attracted to a single pole (not a dipole) along great circles through that pole. He then shows how to calculate the position of the pole if the deviation is known at two known positions (Leuven and Corvo in the Azores): he finds that it must be at latitude 73°2' and longitude 169°34'. Remarkably, he also calculates the longitude difference between the pole and an arbitrary position: he had solved the longitude problem—if his theory had been correct. Further comments on magnetism may be found in an earlier letter to Perrenot[66] and on the later world map.[67] In the Hogenberg portrait (below) his dividers are set on the position of the magnetic pole.

An updated version of the 1554 map of Europe as it appears in the 1595 atlas In 1554 Mercator published the long-awaited wall map of Europe, dedicating it to his friend, now Cardinal, Antoine Perrenot. He had worked at it for more than twelve years, collecting, comparing, collating and rationalising a vast amount of data and the result was a map of unprecedented detail and accuracy.[68] It "attracted more praise from scholars everywhere than any similar geographical work which has ever been brought out."[62] It also sold in large quantities for much of the rest of the century with a second edition in 1572 and a third edition in the atlas of 1595.

The proposed university in Duisburg failed to materialize because the papal licence to found the University was delayed twelve years and by then Duke Wilhelm had lost interest. It was another 90 years before Duisburg had its university. On the other hand, no papal permit was required to establish the Akademisches Gymnasium where, in 1559 Mercator was invited to teach mathematics with cosmography. One year later, in 1560, he secured the appointment of his friend Jan Vermeulen (Molanus) as rector and then blessed Vermeulen's marriage to his daughter Emerantia. His sons were now growing to manhood and he encouraged them to embark on his own profession. Arnold, the eldest, had produced his first map (of Iceland) in 1558 and would later take over the day-to-day running of Mercator's enterprises. Bartholemew, his second son, showed great academic promise and in 1562 (aged 22) he took over the teaching of his father's three-year-long lecture course—after Mercator had taught it once only! Much to Mercator's grief, Bartholemew died young, in 1568 (aged 28). Rumold, the third son, would spend a large part of his life in London's publishing houses providing for Mercator a vital link to the new discoveries of the Elizabethan age. In 1587 Rumold returned to Duisburg and later, in 1594, it fell to his lot to publish Mercator's works posthumously.

In 1564 Mercator published his map of Britain, a map of greatly improved accuracy which far surpassed any of his previous representations. The circumstances were unusual. It is the only map without a dedicatee and in the text engraved on the map he pointedly denies responsibility for the map's authorship and claims that he is merely engraving and printing it for a "very good friend". The identity of neither the author nor the friend has been established but it has been suggested that the map was created by a Scottish Catholic priest called John Elder who smuggled it to French clergy known to Antoine Perrenot, Mercator's friend. Mercator's reticence shows that he was clearly aware of the political nature of the pro-Catholic map which showed all the Catholic religious foundations and omitted those created by Protestant Henry VIII; moreover, it was engraved with text demeaning the history of England and praising that of Catholic Ireland and Scotland. It was invaluable as an accurate guide for the planned Catholic invasion of England by Phillip II of Spain.

As soon as the map of Britain was published Mercator was invited to undertake the surveying and mapping of Lorraine (Lotharingia). This was a new venture for him in the sense that never before had he collected the raw data for a new regional map. He was then 52, already an old man by the norms of that century, and he may well have had reservations about the undertaking. Accompanied by his son Bartholemew, Mercator meticulously triangulated his way around the forests, hills and steep sided valleys of Lorraine, difficult terrain as different from the Low Countries as anything could be. He never committed anything to paper but he may have confided in his friend Ghim who would later write: "The journey through Lorraine gravely imperiled his life and so weakened him that he came very near to a serious breakdown and mental derangement as a result of his terrifying experiences."[62] Mercator returned home to convalesce, leaving Bartholemew to complete the survey. No map was published at the time but Mercator did provide a single drawn copy for the Duke and later he would incorporate this map into his atlas.

The trip to Lorraine in 1564 was a set back for his health but he soon recovered and embarked on his greatest project yet, a project which would extend far beyond his cartographic interests. The first element was the Chronologia,[80] a list of all significant events since the beginning of the world compiled from his literal reading of the Bible and no less than 123 other authors of genealogies and histories of every empire that had ever existed.[81] Mercator was the first to link historical dates of solar and lunar eclipses to Julian dates calculated mathematically from his knowledge of the motions of the sun, moon and Earth. He then fixed the dates of other events in Babylonian, Greek, Hebrew and Roman calendars relative to the eclipses that they recorded. The time origin was fixed from the genealogies of the Bible as 3,965 years before the birth of Christ.[82] This huge volume (400 pages) was greeted with acclaim by scholars throughout Europe and Mercator himself considered it to be his greatest achievement up to that time. On the other hand, the Catholic Church placed the work on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (List of Prohibited Books) because Mercator included the deeds of Martin Luther. Had he published such a work in Louvain he would again be laying himself open to charges of heresy.[83]

The Chronologia developed into an even wider project, the Cosmographia, a description of the whole Universe. Mercator's outline was (1) the creation of the world; (2) the description of the heavens (astronomy and astrology); (3) the description of the earth comprising modern geography, the geography of Ptolemy and the geography of the ancients; (4) genealogy and history of the states; and (5) chronology. Of these the chronology had already been accomplished, the account of the creation and the modern maps would appear in the atlas of 1595, his edition of Ptolemy appeared in 1578 but the ancient geography and the description of the heavens never appeared.[84]

As the Chronologia was going to press in 1569, Mercator also published what was to become his most famous map: Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata ('A new and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation'). As mariners had started to explore the oceans in the Age of Discovery the problem of accurate navigation had become more pressing. Their locations could be a hundred miles out after a long voyage because a course of constant direction at sea (a rhumb line) did not correspond to a straight line on their chart. Mercator's solution was to make the scale of his chart increase with latitude in a very special way such that the rhumb lines became straight lines on his new world map. Exactly how he arrived at the required solution is not recorded in any of his own written works but modern scholars[86] suggest that he used the tables of rhumbs devised by Pedro Nunes.[87] The large size of what was a wall map meant that it did not find favour for use on board ship but, within a hundred years of its creation, the Mercator projection became the standard for marine charts throughout the world and continues to be so used to the present day. On the other hand, the projection is clearly unsuitable as a description of the land masses on account of its manifest distortion at high latitudes and its use is now deprecated: other projections are more suitable.[88] Although several hundred copies of the map were produced[59] it soon became out of date as new discoveries showed the extent of Mercator's inaccuracies (of poorly known lands) and speculations (for example, on the arctic and the southern continent).

Around this time the marshall of Jülich approached Mercator and asked him to prepare a set of European regional maps which would serve for a grand tour by his patron's son, the crown prince Johannes. This remarkable collection has been preserved and is now held in the British Library under the title Atlas of Europe (although Mercator never used such a title). Many of the pages were assembled from dissected Mercator maps and in addition there are thirty maps from the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of Abraham Ortelius.[90]

Apart from a revision of the map of Europe in 1572 there would be no more large wall maps and Mercator began to address the other tasks that he had outlined in the Cosmographia. The first of these was a new definitive version of Ptolemy's maps.[91] That he should wish to do so may seem strange given that, at the same time, he was planning very different modern maps and other mapmakers, such as his friend Abraham Ortelius, had forsaken Ptolemy completely. It was essentially an act of reverence by one scholar for another, a final epitaph for the Ptolemy who had inspired Mercator's love of geography early in his life. He compared the great many editions of the Ptolemy's written Geographia, which described his two projections and listed the latitude and longitude of some 8000 places, as well as the many different versions of the printed maps which had appeared over the previous one hundred years, all with errors and accretions. Once again, this self-imposed diligence delayed publication and the 28 maps of Ptolemy appeared in 1578, after an interval almost ten years. It was accepted by scholars as the "last word", literally and metaphorically, in a chapter of geography which was closed for good.[92]

Mercator now turned to the modern maps, as author but no longer engraver: the practicalities of production of maps and globes had been passed to his sons and grandsons. In 1585 he issued a collection of 51 maps covering France, the Low Countries and Germany. Other maps may have followed in good order had not the misfortunes of life intervened: his wife Barbara died in 1586 and his eldest son Arnold died the following year so that only Rumold and the sons of Arnold were left to carry forward his business. In addition, the time he had available for cartography was reduced by a burst of writing on philosophy and theology: a substantial written work on the Harmonisation[94] of the Gospels[95] as well as commentaries on the epistle of St. Paul and the book of Ezekiel. In 1589, at the age of 77, Mercator had a new lease of life. He took a new wife, Gertrude Vierlings, the wealthy widow of a former mayor of Duisburg (and at the same time he arranged the marriage of Rumold to her daughter). A second collection of 22 maps was published covering Italy, Greece and the Balkans. This volume has a noteworthy preface for it includes mention of Atlas as a mythical king of Mauretania. "I have set this man Atlas," explained Mercator, "so notable for his erudition, humaneness, and wisdom as a model for my imitation."[96] A year later, Mercator had a stroke which left him greatly incapacitated. He struggled with the assistance of his family trying to complete the remaining maps, the ongoing theological publications and a new treatise on the Creation of the World. This last work, which he did succeed in finishing, was the climax of his life's activities, the work which, in his own opinion, surpassed all his other endeavours and provided a framework and rationale for the complete atlas. It was also his last work in a literal sense for he died after two further strokes in 1594.

Epitaph and legacy

Mercator was buried in the church of St. Salvatore in Duisburg where a memorial was erected about fifty years after his death. The main text of the epitaph is a summary of his life lauding him as the foremost mathematician of his time who crafted artistic and accurate globes showing the heaven from the inside and the Earth from the outside ... greatly respected for his wide erudition, particularly in theology, and famous on account of his piety and respectability in life. In addition, on the base of the memorial, there is an epigram:

To the reader: whoever you are, your fears that this small clod of earth lies heavily on the buried Mercator are groundless; the whole Earth is no burden for a man who had the whole weight of her lands on his shoulders and carried her as an Atlas.

Following Mercator's death his family prepared the Atlas for publication—in four months. It was hoped for source of the income that was needed to support them. This work entailed supplementing the maps of the 1585 and 1589 with 28 unpublished maps of Mercator covering the northern countries, creating four maps of the continents and a world map, the printing of Mercator's account of the creation and finally the addition of eulogies and Walter Ghim's biography of Mercator. The title itself provides Mercator's definition of a new meaning for the word "Atlas": Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura which may be translated as "Atlas or cosmographical meditations upon the fabric of the world and the figure of the fabrick'd, or, more colloquially, as Atlas or cosmographical meditations upon the creation of the universe, and the universe as created." Over the years Mercator's definition of atlas has become simply A collection of maps in a volume.

The atlas was not an immediate success. One reason may have been that it was incomplete: Spain was omitted and there were no detailed maps outside Europe. Rumold avowed that a second volume would attend to these deficiencies but it was not forthcoming and the whole project lost momentum; Rumold, who was 55 years old in 1595, was in decline and died in 1599. His family did produce another edition in 1602 but only the text was reset, there were no new maps.[102] Another reason for the failure of the Atlas was the strength of the continuing sales of the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of Abraham Ortelius. Alongside the sumptuous maps of that book Mercator's un-ornamented new maps looked very unattractive. Despite the death of Ortelius in 1598 the Theatrum flourished: in 1602 it was in its thirteenth Latin edition as well as editions in Dutch, Italian, French, German and Spanish. The Mercator atlas seemed destined for oblivion.

The family was clearly in some financial difficulty for, in 1604, Mercator's library of some 1,000 books was sold at a public auction in Leyden (Netherlands). The only known copy of the sale catalogue[104] perished in the war but fortunately a manuscript copy had been made by Van Raemdonck in 1891 and this was rediscovered in 1987.[105] Of the titles identified there are 193 on theology (both Catholic and Lutheran), 217 on history and geography, 202 on mathematics (in its widest sense), 32 on medicine and over 100 simply classified (by Basson) as rare books. The contents of the library provide an insight into Mercator's intellectual studies but the mathematics books are the only ones to have been subjected to scholarly analysis: they cover arithmetic, geometry, trigonometry, surveying, architecture, fortification, astronomy, astrology, time measurement, calendar calculation, scientific instruments, cartography and applications.[106][107] Only one of his own copies has been found—a first edition of Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium annotated in Mercator's hand: this is held by Glasgow University.

The sale catalogue doesn't mention any maps but it is known that the family sold the copper plates to Jodocus Hondius in 1604.[108] He transformed the atlas. Almost 40 extra maps were added (including Spain and Portugal) and in 1606 a new edition appeared under his name but with full acknowledgement that most maps were created by Mercator. The title page now included a picture of Hondius and Mercator together although they had never met. Hondius was an accomplished business man and under his guidance the Atlas was an enormous success; he (followed by his son Henricus, and son-in-law Johannes Janssonius) produced 29 editions between 1609 and 1641, including one in English. In addition they published the atlas in a compact form, the Atlas Minor,[109] which meant that it was readily available to a wide market. As the editions progressed, Mercator's theological comments and his map commentaries disappeared from the atlas and images of King Atlas were replaced by the Titan Atlas. By the final edition the number of his maps in the atlas declined to less than 50 as updated new maps were added. Eventually the atlas became out-of-date and by the middle of the seventeenth century the publications of map-makers such as Joan Blaeu and Frederik de Wit took over.

Mercator's editions of Ptolemy and his theological writings were in print for many years after the demise of the atlas but they too eventually disappeared and it was the Mercator projection which emerged as his sole and greatest legacy.[110] His construction of a chart on which the courses of constant bearing favoured by mariners appeared as straight lines ultimately revolutionised the art of navigation, making it simpler and therefore safer. Mercator left no hints to his method of construction and it was Edward Wright who first clarified the method in his book Certaine Errors (1599)—the relevant error being the erroneous belief that straight lines on conventional charts corresponded to constant courses. Wright's solution was a numerical approximation and it was another 70 years before the projection formula was derived analytically. Wright published a new world map based on the Mercator projection, also in 1599. Slowly, but steadily, charts using the projection appeared throughout the first half of the seventeenth century and by the end of that century chart makers all over the world were using nothing but the Mercator projection, with the aim of showing the oceans and the coastlines in detail without concern for the continental interiors. At some stage the projection made the unfortunate leap to portrayal of the continents and it eventually became the canonical description of the world, despite its manifest distortions at high latitudes.[111] Recently Mercator's projection has been rejected for representations of the world[112] but it remains paramount for nautical charts and its use stands as his enduring legacy.