Ebola (nonfiction)

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) or Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever of humans and other primates caused by ebolaviruses.[1] Signs and symptoms typically start between two days and three weeks after contracting the virus with a fever, sore throat, muscular pain, and headaches. Vomiting, diarrhoea and rash usually follow, along with decreased function of the liver and kidneys. At this time, some people begin to bleed both internally and externally. The disease has a high risk of death, killing 25% to 90% of those infected, with an average of about 50%. This is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss, and typically follows six to 16 days after symptoms appear.

The virus spreads through direct contact with body fluids, such as blood from infected humans or other animals. Spread may also occur from contact with items recently contaminated with bodily fluids. Spread of the disease through the air between primates, including humans, has not been documented in either laboratory or natural conditions. Semen or breast milk of a person after recovery from EVD may carry the virus for several weeks to months. Fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature, able to spread the virus without being affected by it. Other diseases such as malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitis and other viral haemorrhagic fevers may resemble EVD. Blood samples are tested for viral RNA, viral antibodies or for the virus itself to confirm the diagnosis.

Control of outbreaks requires coordinated medical services and community engagement. This includes rapid detection, contact tracing of those who have been exposed, quick access to laboratory services, care for those infected, and proper disposal of the dead through cremation or burial. Samples of body fluids and tissues from people with the disease should be handled with special caution. Prevention includes limiting the spread of disease from infected animals to humans by handling potentially infected bushmeat only while wearing protective clothing, and by thoroughly cooking bushmeat before eating it. It also includes wearing proper protective clothing and washing hands when around a person with the disease. An Ebola vaccine was approved in the United States in December 2019. While there is no approved treatment for Ebola as of 2019, two treatments (REGN-EB3 and mAb114) are associated with improved outcomes. Supportive efforts also improve outcomes. This includes either oral rehydration therapy (drinking slightly sweetened and salty water) or giving intravenous fluids as well as treating symptoms.

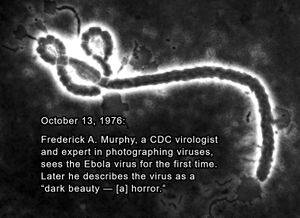

The disease was first identified in 1976, in two simultaneous outbreaks: one in Nzara (a town in South Sudan) and the other in Yambuku (Democratic Republic of the Congo), a village relatively near the Ebola River from which the disease takes its name. EVD outbreaks occur intermittently in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa. From 1976 to 2012, the World Health Organization reports 24 outbreaks involving 2,387 cases with 1,590 deaths. The largest outbreak to date was the epidemic in West Africa, which occurred from December 2013 to January 2016, with 28,646 cases and 11,323 deaths. It was declared no longer an emergency on 29 March 2016.[15] Other outbreaks in Africa began in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in May 2017, and 2018. In July 2019, the World Health Organization declared the Congo Ebola outbreak a world health emergency.

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

External links

- Ebola @ Wikipedia

- Ebola: the First Glimpse of a Virus @ Time