Konrad Zuse (nonfiction): Difference between revisions

(Created page with "thumb|Konrad Zuse.'''Konrad Zuse''' (German: [ˈkɔnʁat ˈtsuːzə]; 22 June 1910 – 18 December 1995) was a German civil engineer, inventor...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

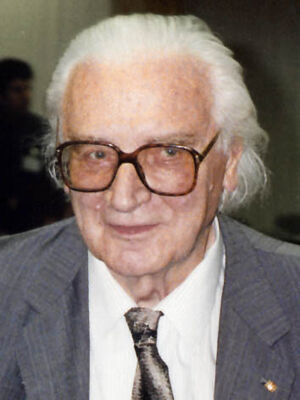

[[File:Konrad_Zuse_(1992).jpg|thumb|Konrad Zuse.]]'''Konrad Zuse''' (German: [ˈkɔnʁat ˈtsuːzə]; 22 June 1910 – 18 December 1995) was a German civil engineer, inventor and computer pioneer. His greatest achievement was the world's first programmable computer; the functional program-controlled Turing-complete Z3 became operational in May 1941. Thanks to this machine and its predecessors, Zuse has often been regarded as the inventor of the modern computer. | [[File:Konrad_Zuse_(1992).jpg|thumb|Konrad Zuse.]]'''Konrad Zuse''' (German: [ˈkɔnʁat ˈtsuːzə]; 22 June 1910 – 18 December 1995) was a German civil engineer, inventor and computer pioneer. His greatest achievement was the world's first programmable computer; the functional program-controlled Turing-complete Z3 became operational in May 1941. Thanks to this machine and its predecessors, Zuse has often been regarded as the inventor of the modern computer. | ||

Zuse was also noted for the S2 computing machine, considered the first process control computer. He founded one of the earliest computer businesses in 1941, producing the Z4, which became the world's first commercial computer. From 1943[8] to 1945 he designed the first high-level programming language, Plankalkül.[10] In 1969, Zuse suggested the concept of a computation-based universe in his book ''Rechnender Raum'' (Calculating Space). | |||

Much of his early work was financed by his family and commerce, but after 1939 he was given resources by the Nazi German government. Due to World War II, Zuse's work went largely unnoticed in the United Kingdom and the United States. Possibly his first documented influence on a US company was IBM's option on his patents in 1946. | |||

Born in Berlin, Germany, on 22 June 1910, he moved with his family in 1912 to East Prussian Braunsberg (now Braniewo in Poland), where his father was a postal clerk. Zuse attended the Collegium Hosianum in Braunsberg. In 1923, the family moved to Hoyerswerda, where he passed his Abitur in 1928, qualifying him to enter university. | Born in Berlin, Germany, on 22 June 1910, he moved with his family in 1912 to East Prussian Braunsberg (now Braniewo in Poland), where his father was a postal clerk. Zuse attended the Collegium Hosianum in Braunsberg. In 1923, the family moved to Hoyerswerda, where he passed his Abitur in 1928, qualifying him to enter university. | ||

He enrolled in the Technische Hochschule Berlin (now Technical University of Berlin) and explored both engineering and architecture, but found them boring. Zuse then pursued civil engineering, graduating in 1935. For a time, he worked for the Ford Motor Company, using his considerable artistic skills in the design of advertisements. He started work as a design engineer at the Henschel aircraft factory in Schönefeld near Berlin. This required the performance of many routine calculations by hand, which he found mind-numbingly boring, leading him to dream of doing them by machine. | He enrolled in the Technische Hochschule Berlin (now Technical University of Berlin) and explored both engineering and architecture, but found them boring. Zuse then pursued civil engineering, graduating in 1935. For a time, he worked for the Ford Motor Company, using his considerable artistic skills in the design of advertisements.[10] He started work as a design engineer at the Henschel aircraft factory in Schönefeld near Berlin. This required the performance of many routine calculations by hand, which he found mind-numbingly boring, leading him to dream of doing them by machine. | ||

Beginning in 1935 he experimented in the construction of computers in his parents' flat on Wrangelstraße 38, moving with them into their new flat on Methfesselstraße 10, the street leading up the Kreuzberg, Berlin. Working in his parents' apartment in 1936, he produced his first attempt, the Z1, a floating point binary mechanical calculator with limited programmability, reading instructions from a perforated 35 mm film. In 1937, Zuse submitted two patents that anticipated a von Neumann architecture. He finished the Z1 in 1938. The Z1 contained some 30,000 metal parts and never worked well due to insufficient mechanical precision. On 30 January 1944, the Z1 and its original blueprints were destroyed with his parents' flat and many neighbouring buildings by a British air raid in World War II. | |||

Between 1987 and 1989, Zuse recreated the Z1, suffering a heart attack midway through the project. It cost 800,000 DM, (approximately $500,000) and required four individuals (including Zuse) to assemble it. Funding for this retrocomputing project was provided by Siemens and a consortium of five companies. | |||

The Z2, Z3, and Z4: | |||

Zuse completed his work entirely independently of other leading computer scientists and mathematicians of his day. Between 1936 and 1945, he was in near-total intellectual isolation. In 1939, Zuse was called to military service, where he was given the resources to ultimately build the Z2. In September 1940 Zuse presented the Z2, covering several rooms in the parental flat, to experts of the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt (DVL; i.e. German Research Institute for Aviation). The Z2 was a revised version of the Z1 using telephone relays. | |||

The DVL granted research subsidies so that in 1941 Zuse started a company, Zuse Apparatebau (Zuse Apparatus Construction), to manufacture his machines, renting a workshop on the opposite side in Methfesselstraße 7 and stretching through the block to Belle-Alliance Straße 29 (renamed and renumbered as Mehringdamm 84 in 1947). | |||

Improving on the basic Z2 machine, he built the Z3 in 1941. On 12 May 1941 Zuse presented the Z3, built in his workshop, to the public. The Z3 was a binary 22-bit floating point calculator featuring programmability with loops but without conditional jumps, with memory and a calculation unit based on telephone relays. The telephone relays used in his machines were largely collected from discarded stock. Despite the absence of conditional jumps, the Z3 was a Turing complete computer. However, Turing-completeness was never considered by Zuse (who had practical applications in mind) and only demonstrated in 1998 (see History of computing hardware). | |||

The Z3, the first fully operational electromechanical computer, was partially financed by German government-supported DVL, which wanted their extensive calculations automated. A request by his co-worker Helmut Schreyer—who had helped Zuse build the Z3 prototype in 1938—for government funding for an electronic successor to the Z3 was denied as "strategically unimportant". | |||

In | In 1937, Schreyer had advised Zuse to use vacuum tubes as switching elements; Zuse at this time considered it a crazy idea ("Schnapsidee" in his own words). Zuse's workshop on Methfesselstraße 7 (with the Z3) was destroyed in an Allied Air raid in late 1943 and the parental flat with Z1 and Z2 on 30 January the following year, whereas the successor Z4, which Zuse had begun constructing in 1942 in new premises in the Industriehof on Oranienstraße 6, remained intact. On 3 February 1945, aerial bombing caused devastating destruction in the Luisenstadt, the area around Oranienstraße, including neighbouring houses. This event effectively brought Zuse's research and development to a complete halt. The partially finished, relay-based Z4 was packed and moved from Berlin on 14 February, only arriving in Göttingen two weeks later. | ||

Work on the Z4 could not be resumed immediately in the extreme privation of post-war Germany, and it was not until 1949 that he was able to resume work on it. He showed it to the mathematician Eduard Stiefel of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) Zürich) who ordered one in 1950. On 8 November 1949, Zuse KG was founded. The Z4 was delivered to ETH Zurich on 12 July 1950, and proved very reliable. | |||

S1 and S2: | |||

In | In 1940, the German government began funding him through the Aerodynamische Versuchsanstalt (AVA, Aerodynamic Research Institute, forerunner of the DLR), which used his work for the production of glide bombs. Zuse built the S1 and S2 computing machines, which were special purpose devices which computed aerodynamic corrections to the wings of radio-controlled flying bombs. The S2 featured an integrated analog-to-digital converter under program control, making it the first process-controlled computer. | ||

These machines contributed to the Henschel Werke Hs 293 and Hs 294 guided missiles developed by the German military between 1941 and 1945, which were the precursors to the modern cruise missile. The circuit design of the S1 was the predecessor of Zuse's Z11. Zuse believed that these machines had been captured by occupying Soviet troops in 1945. | |||

Plankalkül: | |||

Zuse' | While working on his Z4 computer, Zuse realised that programming in machine code was too complicated. He started working on a PhD thesis[26] containing groundbreaking research years ahead of its time, mainly the first high-level programming language, ''Plankalkül'' ("Plan Calculus") and, as an elaborate example program, the first real computer chess engine. After the 1945 Luisenstadt bombing, he flew from Berlin for the rural Allgäu, and, unable to do any hardware development, he continued working on the Plankalkül, eventually publishing some brief excerpts of his thesis in 1948 and 1959; the work in its entirety, however, remained unpublished until 1972. The PhD thesis was submitted at University of Augsburg, but rejected for formal reasons, because Zuse forgot to pay the 400 Mark university enrollment fee. (The rejection did not bother him.) Plankalkül slightly influenced the design of ALGOL 58 but was itself implemented only in 1975 in a dissertation by Joachim Hohmann. Heinz Rutishauser, one of the inventors of ALGOL, wrote: "The very first attempt to devise an algorithmic language was undertaken in 1948 by K. Zuse. His notation was quite general, but the proposal never attained the consideration it deserved". Further implementations followed in 1998 and then in 2000 by a team from the Free University of Berlin. Donald Knuth suggested a thought experiment: What might have happened had the bombing not taken place, and had the PhD thesis accordingly been published as planned? | ||

Personal life: | |||

Konrad Zuse married Gisela Brandes in January 1945, employing a carriage, himself dressed in tailcoat and top hat and with Gisela in a wedding veil, for Zuse attached importance to a "noble ceremony". Their son Horst, the first of five children, was born in November 1945. | |||

While Zuse never became a member of the Nazi Party, he is not known to have expressed any doubts or qualms about working for the Nazi war effort. Much later, he suggested that in modern times, the best scientists and engineers usually have to choose between either doing their work for more or less questionable business and military interests in a Faustian bargain, or not pursuing their line of work at all. | |||

According to the memoirs of the German computer pioneer Heinz Billing from the Max Planck Institute for Physics, published by Genscher, Düsseldorf, there was a meeting between Alan Turing and Konrad Zuse. It took place in Göttingen in 1947. The encounter had the form of a colloquium. Participants were Womersley, Turing, Porter from England and a few German researchers like Zuse, Walther, and Billing. (For more details see Herbert Bruderer, Konrad Zuse und die Schweiz). | |||

After he retired, he focused on his hobby of painting. | |||

Zuse was an atheist. | |||

Zuse died on 18 December 1995 in Hünfeld, Germany (near Fulda) from heart failure. | |||

Zuse the entrepreneur: | |||

During World War 2, Zuse founded one of the earliest computer companies: the Zuse-Ingenieurbüro Hopferau. Capital was raised in 1946 through ETH Zurich and an IBM option on Zuse's patents. | |||

Zuse founded another company, Zuse KG in Haunetal-Neukirchen in 1949; in 1957 the company’s head office moved to Bad Hersfeld. The Z4 was finished and delivered to the ETH Zurich, Switzerland in September 1950. At that time, it was the only working computer in continental Europe, and the second computer in the world to be sold, beaten only by the BINAC, which never worked properly after it was delivered. Other computers, all numbered with a leading Z, up to Z43, were built by Zuse and his company. Notable are the Z11, which was sold to the optics industry and to universities, and the Z22, the first computer with a memory based on magnetic storage. | |||

By 1967, the Zuse KG had built a total of 251 computers. Owing to financial problems, the company was then sold to Siemens. | |||

Calculating Space: | |||

In 1967, Zuse also suggested that the universe itself is running on a cellular automaton or similar computational structure (digital physics); in 1969, he published the book ''Rechnender Raum'' (translated into English as Calculating Space). This idea has attracted a lot of attention, since there is no physical evidence against Zuse's thesis. Edward Fredkin (1980s), Jürgen Schmidhuber (1990s), and others have expanded on it. | |||

== In the News == | == In the News == | ||

Revision as of 20:32, 8 May 2018

Konrad Zuse (German: [ˈkɔnʁat ˈtsuːzə]; 22 June 1910 – 18 December 1995) was a German civil engineer, inventor and computer pioneer. His greatest achievement was the world's first programmable computer; the functional program-controlled Turing-complete Z3 became operational in May 1941. Thanks to this machine and its predecessors, Zuse has often been regarded as the inventor of the modern computer.

Zuse was also noted for the S2 computing machine, considered the first process control computer. He founded one of the earliest computer businesses in 1941, producing the Z4, which became the world's first commercial computer. From 1943[8] to 1945 he designed the first high-level programming language, Plankalkül.[10] In 1969, Zuse suggested the concept of a computation-based universe in his book Rechnender Raum (Calculating Space).

Much of his early work was financed by his family and commerce, but after 1939 he was given resources by the Nazi German government. Due to World War II, Zuse's work went largely unnoticed in the United Kingdom and the United States. Possibly his first documented influence on a US company was IBM's option on his patents in 1946.

Born in Berlin, Germany, on 22 June 1910, he moved with his family in 1912 to East Prussian Braunsberg (now Braniewo in Poland), where his father was a postal clerk. Zuse attended the Collegium Hosianum in Braunsberg. In 1923, the family moved to Hoyerswerda, where he passed his Abitur in 1928, qualifying him to enter university.

He enrolled in the Technische Hochschule Berlin (now Technical University of Berlin) and explored both engineering and architecture, but found them boring. Zuse then pursued civil engineering, graduating in 1935. For a time, he worked for the Ford Motor Company, using his considerable artistic skills in the design of advertisements.[10] He started work as a design engineer at the Henschel aircraft factory in Schönefeld near Berlin. This required the performance of many routine calculations by hand, which he found mind-numbingly boring, leading him to dream of doing them by machine.

Beginning in 1935 he experimented in the construction of computers in his parents' flat on Wrangelstraße 38, moving with them into their new flat on Methfesselstraße 10, the street leading up the Kreuzberg, Berlin. Working in his parents' apartment in 1936, he produced his first attempt, the Z1, a floating point binary mechanical calculator with limited programmability, reading instructions from a perforated 35 mm film. In 1937, Zuse submitted two patents that anticipated a von Neumann architecture. He finished the Z1 in 1938. The Z1 contained some 30,000 metal parts and never worked well due to insufficient mechanical precision. On 30 January 1944, the Z1 and its original blueprints were destroyed with his parents' flat and many neighbouring buildings by a British air raid in World War II.

Between 1987 and 1989, Zuse recreated the Z1, suffering a heart attack midway through the project. It cost 800,000 DM, (approximately $500,000) and required four individuals (including Zuse) to assemble it. Funding for this retrocomputing project was provided by Siemens and a consortium of five companies.

The Z2, Z3, and Z4:

Zuse completed his work entirely independently of other leading computer scientists and mathematicians of his day. Between 1936 and 1945, he was in near-total intellectual isolation. In 1939, Zuse was called to military service, where he was given the resources to ultimately build the Z2. In September 1940 Zuse presented the Z2, covering several rooms in the parental flat, to experts of the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt (DVL; i.e. German Research Institute for Aviation). The Z2 was a revised version of the Z1 using telephone relays.

The DVL granted research subsidies so that in 1941 Zuse started a company, Zuse Apparatebau (Zuse Apparatus Construction), to manufacture his machines, renting a workshop on the opposite side in Methfesselstraße 7 and stretching through the block to Belle-Alliance Straße 29 (renamed and renumbered as Mehringdamm 84 in 1947).

Improving on the basic Z2 machine, he built the Z3 in 1941. On 12 May 1941 Zuse presented the Z3, built in his workshop, to the public. The Z3 was a binary 22-bit floating point calculator featuring programmability with loops but without conditional jumps, with memory and a calculation unit based on telephone relays. The telephone relays used in his machines were largely collected from discarded stock. Despite the absence of conditional jumps, the Z3 was a Turing complete computer. However, Turing-completeness was never considered by Zuse (who had practical applications in mind) and only demonstrated in 1998 (see History of computing hardware).

The Z3, the first fully operational electromechanical computer, was partially financed by German government-supported DVL, which wanted their extensive calculations automated. A request by his co-worker Helmut Schreyer—who had helped Zuse build the Z3 prototype in 1938—for government funding for an electronic successor to the Z3 was denied as "strategically unimportant".

In 1937, Schreyer had advised Zuse to use vacuum tubes as switching elements; Zuse at this time considered it a crazy idea ("Schnapsidee" in his own words). Zuse's workshop on Methfesselstraße 7 (with the Z3) was destroyed in an Allied Air raid in late 1943 and the parental flat with Z1 and Z2 on 30 January the following year, whereas the successor Z4, which Zuse had begun constructing in 1942 in new premises in the Industriehof on Oranienstraße 6, remained intact. On 3 February 1945, aerial bombing caused devastating destruction in the Luisenstadt, the area around Oranienstraße, including neighbouring houses. This event effectively brought Zuse's research and development to a complete halt. The partially finished, relay-based Z4 was packed and moved from Berlin on 14 February, only arriving in Göttingen two weeks later.

Work on the Z4 could not be resumed immediately in the extreme privation of post-war Germany, and it was not until 1949 that he was able to resume work on it. He showed it to the mathematician Eduard Stiefel of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) Zürich) who ordered one in 1950. On 8 November 1949, Zuse KG was founded. The Z4 was delivered to ETH Zurich on 12 July 1950, and proved very reliable.

S1 and S2:

In 1940, the German government began funding him through the Aerodynamische Versuchsanstalt (AVA, Aerodynamic Research Institute, forerunner of the DLR), which used his work for the production of glide bombs. Zuse built the S1 and S2 computing machines, which were special purpose devices which computed aerodynamic corrections to the wings of radio-controlled flying bombs. The S2 featured an integrated analog-to-digital converter under program control, making it the first process-controlled computer.

These machines contributed to the Henschel Werke Hs 293 and Hs 294 guided missiles developed by the German military between 1941 and 1945, which were the precursors to the modern cruise missile. The circuit design of the S1 was the predecessor of Zuse's Z11. Zuse believed that these machines had been captured by occupying Soviet troops in 1945.

Plankalkül:

While working on his Z4 computer, Zuse realised that programming in machine code was too complicated. He started working on a PhD thesis[26] containing groundbreaking research years ahead of its time, mainly the first high-level programming language, Plankalkül ("Plan Calculus") and, as an elaborate example program, the first real computer chess engine. After the 1945 Luisenstadt bombing, he flew from Berlin for the rural Allgäu, and, unable to do any hardware development, he continued working on the Plankalkül, eventually publishing some brief excerpts of his thesis in 1948 and 1959; the work in its entirety, however, remained unpublished until 1972. The PhD thesis was submitted at University of Augsburg, but rejected for formal reasons, because Zuse forgot to pay the 400 Mark university enrollment fee. (The rejection did not bother him.) Plankalkül slightly influenced the design of ALGOL 58 but was itself implemented only in 1975 in a dissertation by Joachim Hohmann. Heinz Rutishauser, one of the inventors of ALGOL, wrote: "The very first attempt to devise an algorithmic language was undertaken in 1948 by K. Zuse. His notation was quite general, but the proposal never attained the consideration it deserved". Further implementations followed in 1998 and then in 2000 by a team from the Free University of Berlin. Donald Knuth suggested a thought experiment: What might have happened had the bombing not taken place, and had the PhD thesis accordingly been published as planned?

Personal life:

Konrad Zuse married Gisela Brandes in January 1945, employing a carriage, himself dressed in tailcoat and top hat and with Gisela in a wedding veil, for Zuse attached importance to a "noble ceremony". Their son Horst, the first of five children, was born in November 1945.

While Zuse never became a member of the Nazi Party, he is not known to have expressed any doubts or qualms about working for the Nazi war effort. Much later, he suggested that in modern times, the best scientists and engineers usually have to choose between either doing their work for more or less questionable business and military interests in a Faustian bargain, or not pursuing their line of work at all.

According to the memoirs of the German computer pioneer Heinz Billing from the Max Planck Institute for Physics, published by Genscher, Düsseldorf, there was a meeting between Alan Turing and Konrad Zuse. It took place in Göttingen in 1947. The encounter had the form of a colloquium. Participants were Womersley, Turing, Porter from England and a few German researchers like Zuse, Walther, and Billing. (For more details see Herbert Bruderer, Konrad Zuse und die Schweiz).

After he retired, he focused on his hobby of painting.

Zuse was an atheist.

Zuse died on 18 December 1995 in Hünfeld, Germany (near Fulda) from heart failure.

Zuse the entrepreneur:

During World War 2, Zuse founded one of the earliest computer companies: the Zuse-Ingenieurbüro Hopferau. Capital was raised in 1946 through ETH Zurich and an IBM option on Zuse's patents.

Zuse founded another company, Zuse KG in Haunetal-Neukirchen in 1949; in 1957 the company’s head office moved to Bad Hersfeld. The Z4 was finished and delivered to the ETH Zurich, Switzerland in September 1950. At that time, it was the only working computer in continental Europe, and the second computer in the world to be sold, beaten only by the BINAC, which never worked properly after it was delivered. Other computers, all numbered with a leading Z, up to Z43, were built by Zuse and his company. Notable are the Z11, which was sold to the optics industry and to universities, and the Z22, the first computer with a memory based on magnetic storage.

By 1967, the Zuse KG had built a total of 251 computers. Owing to financial problems, the company was then sold to Siemens.

Calculating Space:

In 1967, Zuse also suggested that the universe itself is running on a cellular automaton or similar computational structure (digital physics); in 1969, he published the book Rechnender Raum (translated into English as Calculating Space). This idea has attracted a lot of attention, since there is no physical evidence against Zuse's thesis. Edward Fredkin (1980s), Jürgen Schmidhuber (1990s), and others have expanded on it.

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

External links:

- Konrad Zuse @ Wikipedia

Attribution: