Giordano Bruno (nonfiction): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

In addition to cosmology, Bruno also wrote extensively on the art of memory, a loosely organized group of mnemonic techniques and principles. | In addition to cosmology, Bruno also wrote extensively on the art of memory, a loosely organized group of mnemonic techniques and principles. | ||

Historian Frances Yates argues that Bruno was deeply influenced by Arab astrology (particularly the philosophy of Averroes), Neoplatonism, Renaissance Hermeticism, and legends surrounding the Egyptian god Thoth. | Historian Frances Yates argues that Bruno was deeply influenced by Arab astrology (particularly the philosophy of [[Averroes (nonfiction)|Averroes]]), Neoplatonism, Renaissance Hermeticism, and legends surrounding the Egyptian god Thoth. | ||

Other studies of Bruno have focused on his qualitative approach to mathematics and his application of the spatial concepts of geometry to language. | Other studies of Bruno have focused on his qualitative approach to mathematics and his application of the spatial concepts of geometry to language. | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

== Nonfiction cross-reference == | == Nonfiction cross-reference == | ||

* [[Averroes (nonfiction)]] | |||

External links: | External links: | ||

Revision as of 18:37, 24 March 2017

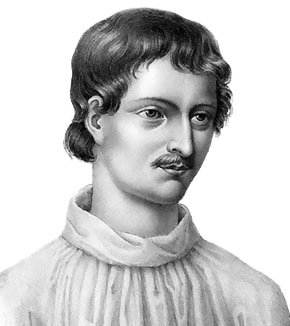

Giordano Bruno (Italian: [dʒorˈdano ˈbruno]; Latin: Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; 1 January 1548 – 17 February 1600), born Filippo Bruno, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, mathematician, poet, and cosmological theorist.

He is remembered for his cosmological theories, which conceptually extended the then novel Copernican model. He proposed that the stars were just distant suns surrounded by their own exoplanets and raised the possibility that these planets could even foster life of their own (a philosophical position known as cosmic pluralism). He also insisted that the universe is in fact infinite and could have no celestial body at its "center".

Bruno moved to Venice in March 1592. For about two months he served as an in-house tutor to Mocenigo. When Bruno announced his plan to leave Venice to his host, the latter, who was unhappy with the teachings he had received and had apparently come to dislike Bruno, denounced him to the Venetian Inquisition, which had Bruno arrested on 22 May 1592. Among the numerous charges of blasphemy and heresy brought against him in Venice, based on Mocenigo's denunciation, was his belief in the plurality of worlds, as well as accusations of personal misconduct.

Beginning in 1593, Bruno was tried for heresy by the Roman Inquisition on charges including denial of several core Catholic doctrines, including eternal damnation, the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, the virginity of Mary, and transubstantiation. Bruno's pantheism was also a matter of grave concern.

The Inquisition found him guilty, and he was burned at the stake in Rome's Campo de' Fiori in 1600.

After his death, he gained considerable fame, being particularly celebrated by 19th- and early 20th-century commentators who regarded him as a martyr for science, although historians have debated the extent to which his heresy trial was a response to his astronomical views or to other aspects of his philosophy and theology.

Bruno's case is still considered a landmark in the history of free thought and the emerging sciences.

In addition to cosmology, Bruno also wrote extensively on the art of memory, a loosely organized group of mnemonic techniques and principles.

Historian Frances Yates argues that Bruno was deeply influenced by Arab astrology (particularly the philosophy of Averroes), Neoplatonism, Renaissance Hermeticism, and legends surrounding the Egyptian god Thoth.

Other studies of Bruno have focused on his qualitative approach to mathematics and his application of the spatial concepts of geometry to language.

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

External links:

- Giordano Bruno @ Wikipedia

Attribution: