Stanislaw Ulam (nonfiction): Difference between revisions

(Created page with "Stanisław Marcin Ulam (pronounced ['staɲiswaf 'mart͡ɕin 'ulam]; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American mathematician. He participated in the Manhattan Proj...") |

No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

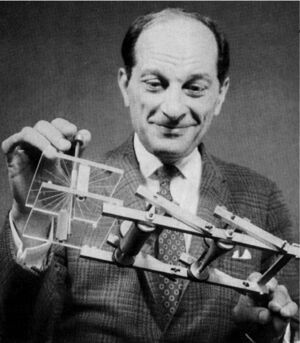

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (pronounced ['staɲiswaf 'mart͡ɕin 'ulam]; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American mathematician. He participated in the [[Manhattan Project (nonfiction)|Manhattan Project]], originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, discovered the concept of [[Cellular automaton (nonfiction)|cellular automata]], invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion. In pure and applied mathematics, he proved some theorems and proposed several conjectures. | [[File:Stanislaw Ulam holding FERMIAC.jpg|thumb|Stan Ulam Holding the FERMIAC.]]'''Stanisław Marcin Ulam''' (pronounced ['staɲiswaf 'mart͡ɕin 'ulam]; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American mathematician. He participated in the [[Manhattan Project (nonfiction)|Manhattan Project]], originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, discovered the concept of [[Cellular automaton (nonfiction)|cellular automata]], invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion. In pure and applied mathematics, he proved some theorems and proposed several conjectures. | ||

Born into a wealthy Polish Jewish family, Ulam studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute, where he earned his PhD in 1933 under the supervision of Kazimierz Kuratowski. In 1935, John von Neumann, whom Ulam had met in Warsaw, invited him to come to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, for a few months. From 1936 to 1939, he spent summers in Poland and academic years at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he worked to establish important results regarding ergodic theory. On 20 August 1939, he sailed for America for the last time with his 17-year-old brother Adam Ulam. He became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1940, and a United States citizen in 1941. | Born into a wealthy Polish Jewish family, Ulam studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute, where he earned his PhD in 1933 under the supervision of [[Kazimierz Kuratowski (nonfiction)|Kazimierz Kuratowski]]. In 1935, [[John von Neumann (nonfiction)|John von Neumann]], whom Ulam had met in Warsaw, invited him to come to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, for a few months. From 1936 to 1939, he spent summers in Poland and academic years at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he worked to establish important results regarding ergodic theory. On 20 August 1939, he sailed for America for the last time with his 17-year-old brother Adam Ulam. He became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1940, and a United States citizen in 1941. | ||

In October 1943, he received an invitation from Hans Bethe to join the Manhattan Project at the secret Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. There, he worked on the hydrodynamic calculations to predict the behavior of the explosive lenses that were needed by an implosion-type weapon. He was assigned to Edward Teller's group, where he worked on Teller's "Super" bomb for Teller and [[Enrico Fermi (nonfiction)|Enrico Fermi]]. After the war he left to become an associate professor at the University of Southern California, but returned to Los Alamos in 1946 to work on thermonuclear weapons. With the aid of a cadre of female "computers", including his wife Françoise Aron Ulam, he found that Teller's "Super" design was unworkable. In January 1951, Ulam and Teller came up with the Teller–Ulam design, which is the basis for all thermonuclear weapons. | In October 1943, he received an invitation from [[Hans Bethe (nonfiction)|Hans Bethe]] to join the [[Manhattan Project (nonfiction)|Manhattan Project]] at the secret Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. There, he worked on the hydrodynamic calculations to predict the behavior of the explosive lenses that were needed by an implosion-type weapon. He was assigned to [[Edward Teller (nonfiction)|Edward Teller]]'s group, where he worked on Teller's "Super" bomb for Teller and [[Enrico Fermi (nonfiction)|Enrico Fermi]]. After the war he left to become an associate professor at the University of Southern California, but returned to Los Alamos in 1946 to work on thermonuclear weapons. With the aid of a cadre of female "computers", including his wife Françoise Aron Ulam, he found that [[Edward Teller (nonfiction)|Teller]]'s "Super" design was unworkable. In January 1951, Ulam and Teller came up with the Teller–Ulam design, which is the basis for all thermonuclear weapons. | ||

Ulam considered the problem of nuclear propulsion of rockets, which was pursued by Project Rover, and proposed, as an alternative to Rover's nuclear thermal rocket, to harness small nuclear explosions for propulsion, which became Project Orion. With Fermi, John Pasta, and Mary Tsingou, Ulam studied the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem, which became the inspiration for the field of non-linear science. He is probably best known for | Ulam considered the problem of nuclear propulsion of rockets, which was pursued by Project Rover, and proposed, as an alternative to Rover's nuclear thermal rocket, to harness small nuclear explosions for propulsion, which became Project Orion. With [[Enrico Fermi (nonfiction)|Fermi]], John Pasta, and Mary Tsingou, Ulam studied the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem, which became the inspiration for the field of non-linear science. He is probably best known for realizing that electronic computers made it practical to apply statistical methods to functions without known solutions, and as computers have developed, the Monte Carlo method has become a common and standard approach to many problems. | ||

== In the News == | == In the News == | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

== Fiction cross-reference == | == Fiction cross-reference == | ||

* [[Gnomon mathematics]] | |||

* [[Mathematics]] | |||

== Nonfiction cross-reference == | == Nonfiction cross-reference == | ||

| Line 18: | Line 21: | ||

* [[Cellular automaton (nonfiction)]] | * [[Cellular automaton (nonfiction)]] | ||

* [[Enrico Fermi (nonfiction)]] | * [[Enrico Fermi (nonfiction)]] | ||

* [[Kazimierz Kuratowski (nonfiction)]] | |||

* [[Manhattan Project (nonfiction)]] | * [[Manhattan Project (nonfiction)]] | ||

* [[Mathematics (nonfiction)]] | * [[Mathematics (nonfiction)]] | ||

* [[Edward Teller (nonfiction)]] | |||

* [[John von Neumann (nonfiction)]] | |||

External links: | External links: | ||

| Line 25: | Line 31: | ||

* [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanislaw_Ulam Stanislaw Ulam] @ Wikipedia | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanislaw_Ulam Stanislaw Ulam] @ Wikipedia | ||

[[Category:Nonfiction (nonfiction)]] | [[Category:Nonfiction (nonfiction)]] | ||

[[Category:Mathematicians (nonfiction)]] | [[Category:Mathematicians (nonfiction)]] | ||

[[Category:People (nonfiction)]] | [[Category:People (nonfiction)]] | ||

Latest revision as of 22:00, 27 November 2017

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (pronounced ['staɲiswaf 'mart͡ɕin 'ulam]; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American mathematician. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, discovered the concept of cellular automata, invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion. In pure and applied mathematics, he proved some theorems and proposed several conjectures.

Born into a wealthy Polish Jewish family, Ulam studied mathematics at the Lwów Polytechnic Institute, where he earned his PhD in 1933 under the supervision of Kazimierz Kuratowski. In 1935, John von Neumann, whom Ulam had met in Warsaw, invited him to come to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, for a few months. From 1936 to 1939, he spent summers in Poland and academic years at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he worked to establish important results regarding ergodic theory. On 20 August 1939, he sailed for America for the last time with his 17-year-old brother Adam Ulam. He became an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1940, and a United States citizen in 1941.

In October 1943, he received an invitation from Hans Bethe to join the Manhattan Project at the secret Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. There, he worked on the hydrodynamic calculations to predict the behavior of the explosive lenses that were needed by an implosion-type weapon. He was assigned to Edward Teller's group, where he worked on Teller's "Super" bomb for Teller and Enrico Fermi. After the war he left to become an associate professor at the University of Southern California, but returned to Los Alamos in 1946 to work on thermonuclear weapons. With the aid of a cadre of female "computers", including his wife Françoise Aron Ulam, he found that Teller's "Super" design was unworkable. In January 1951, Ulam and Teller came up with the Teller–Ulam design, which is the basis for all thermonuclear weapons.

Ulam considered the problem of nuclear propulsion of rockets, which was pursued by Project Rover, and proposed, as an alternative to Rover's nuclear thermal rocket, to harness small nuclear explosions for propulsion, which became Project Orion. With Fermi, John Pasta, and Mary Tsingou, Ulam studied the Fermi–Pasta–Ulam–Tsingou problem, which became the inspiration for the field of non-linear science. He is probably best known for realizing that electronic computers made it practical to apply statistical methods to functions without known solutions, and as computers have developed, the Monte Carlo method has become a common and standard approach to many problems.

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

- Cellular automaton (nonfiction)

- Enrico Fermi (nonfiction)

- Kazimierz Kuratowski (nonfiction)

- Manhattan Project (nonfiction)

- Mathematics (nonfiction)

- Edward Teller (nonfiction)

- John von Neumann (nonfiction)

External links:

- Stanislaw Ulam @ Wikipedia