Bernardino Telesio (nonfiction)

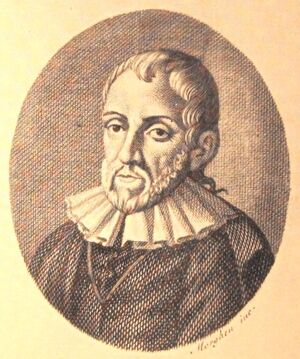

Bernardino Telesio (Italian: [bernarˈdiːno teˈlɛːzjo]) (7 November 1509 – 2 October 1588) was an Italian philosopher and natural scientist. While his natural theories were later disproven, his emphasis on observation made him the "first of the moderns" who eventually developed the scientific method.

His studies included all the wide range of subjects, classics, science and philosophy, which constituted the curriculum of the Renaissance savants. Thus equipped, he began his attack upon the medieval Aristotelianism which then flourished in Padua and Bologna.

For a time he lived in the household of Alfonso III Carafa, Duke of Nocera. In 1563, or perhaps two years later, appeared his great work De Rerum Natura Iuxta Propria Principia (On the Nature of Things according to their Own Principles), which was followed by a large number of scientific and philosophical works of subsidiary importance. The heterodox views which he maintained aroused the anger of the Church on behalf of its cherished Aristotelianism, and a short time after his death his books were placed on the Index.

Instead of postulating matter and form, he bases existence on matter and force. This force has two opposing elements: heat, which expands, and cold, which contracts. These two processes account for all the diverse forms and types of existence, while the mass on which the force operates remains the same. The harmony of the whole consists in this, that each separate thing develops in and for itself in accordance with its own nature while at the same time its motion benefits the rest.

When Telesio went on to explain the relation of mind and matter, he was still more heterodox. Material forces are, by hypothesis, capable of feeling; matter also must have been from the first endowed with consciousness. For consciousness exists, and could not have been developed out of nothing. This leads him to a form of hylozoism. Again, the soul is influenced by material conditions; consequently the soul must have a material existence. He further held that all knowledge is sensation ("non ratione sed sensu") and that intelligence is, therefore, an agglomeration of isolated data, given by the senses.

The whole system of Telesio shows lacunae in argument, and ignorance of essential facts, but at the same time it is a forerunner of all subsequent empiricism, scientific and philosophical, and marks clearly the period of transition from authority and reason to experiment and individual responsibility.

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

External links:

- Bernardino Telesio @ Wikipedia