Rosetta Stone (nonfiction): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The stone was carved during the Hellenistic period and is believed to have originally been displayed within a temple, possibly at nearby Sais, Egypt. It was probably moved in late antiquity or during the Mameluk period, and was eventually used as building material in the construction of Fort Julien near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta. It was discovered there in July 1799 by French soldier Pierre-François Bouchard during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt. It was the first Ancient Egyptian bilingual text recovered in modern times, and it aroused widespread public interest with its potential to decipher this previously untranslated hieroglyphic script. Lithographic copies and plaster casts began circulating among European museums and scholars. The British defeated the French and took the stone to London under the Capitulation of Alexandria in 1801. It has been on public display at the British Museum almost continuously since 1802 and is the most visited object there. | The stone was carved during the Hellenistic period and is believed to have originally been displayed within a temple, possibly at nearby Sais, Egypt. It was probably moved in late antiquity or during the Mameluk period, and was eventually used as building material in the construction of Fort Julien near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta. It was discovered there in July 1799 by French soldier Pierre-François Bouchard during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt. It was the first Ancient Egyptian bilingual text recovered in modern times, and it aroused widespread public interest with its potential to decipher this previously untranslated hieroglyphic script. Lithographic copies and plaster casts began circulating among European museums and scholars. The British defeated the French and took the stone to London under the Capitulation of Alexandria in 1801. It has been on public display at the British Museum almost continuously since 1802 and is the most visited object there. | ||

Study of the decree was already under way when the first full translation of the Greek text appeared in 1803. [[Jean-François Champollion ( | Study of the decree was already under way when the first full translation of the Greek text appeared in 1803. [[Jean-François Champollion (nonfiction)|Jean-François Champollion]] announced the transliteration of the Egyptian scripts in Paris in 1822; it took longer still before scholars were able to read Ancient Egyptian inscriptions and literature confidently. Major advances in the decoding were recognition that the stone offered three versions of the same text (1799); that the demotic text used phonetic characters to spell foreign names (1802); that the hieroglyphic text did so as well, and had pervasive similarities to the demotic (1814); and that phonetic characters were also used to spell native Egyptian words (1822–1824). | ||

Three other fragmentary copies of the same decree were discovered later, and several similar Egyptian bilingual or trilingual inscriptions are now known, including three slightly earlier Ptolemaic decrees: the Decree of Alexandria in 243 BC, the Decree of Canopus in 238 BC, and the Memphis decree of Ptolemy IV, c. 218 BC. The Rosetta Stone is no longer unique, but it was the essential key to modern understanding of ancient Egyptian literature and civilisation. The term Rosetta Stone is now used to refer to the essential clue to a new field of knowledge. | Three other fragmentary copies of the same decree were discovered later, and several similar Egyptian bilingual or trilingual inscriptions are now known, including three slightly earlier Ptolemaic decrees: the Decree of Alexandria in 243 BC, the Decree of Canopus in 238 BC, and the Memphis decree of Ptolemy IV, c. 218 BC. The Rosetta Stone is no longer unique, but it was the essential key to modern understanding of ancient Egyptian literature and civilisation. The term Rosetta Stone is now used to refer to the essential clue to a new field of knowledge. | ||

Revision as of 04:30, 27 September 2019

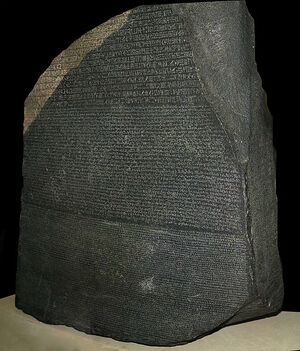

The Rosetta Stone is a granodiorite stele discovered in 1799 which is inscribed with three versions of a decree issued at Memphis, Egypt in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Ancient Egyptian using hieroglyphic and demotic scripts, while the bottom is in Ancient Greek. The decree has only minor differences among the three versions, so the Rosetta Stone became key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, thereby opening a window into ancient Egyptian history.

The stone was carved during the Hellenistic period and is believed to have originally been displayed within a temple, possibly at nearby Sais, Egypt. It was probably moved in late antiquity or during the Mameluk period, and was eventually used as building material in the construction of Fort Julien near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta. It was discovered there in July 1799 by French soldier Pierre-François Bouchard during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt. It was the first Ancient Egyptian bilingual text recovered in modern times, and it aroused widespread public interest with its potential to decipher this previously untranslated hieroglyphic script. Lithographic copies and plaster casts began circulating among European museums and scholars. The British defeated the French and took the stone to London under the Capitulation of Alexandria in 1801. It has been on public display at the British Museum almost continuously since 1802 and is the most visited object there.

Study of the decree was already under way when the first full translation of the Greek text appeared in 1803. Jean-François Champollion announced the transliteration of the Egyptian scripts in Paris in 1822; it took longer still before scholars were able to read Ancient Egyptian inscriptions and literature confidently. Major advances in the decoding were recognition that the stone offered three versions of the same text (1799); that the demotic text used phonetic characters to spell foreign names (1802); that the hieroglyphic text did so as well, and had pervasive similarities to the demotic (1814); and that phonetic characters were also used to spell native Egyptian words (1822–1824).

Three other fragmentary copies of the same decree were discovered later, and several similar Egyptian bilingual or trilingual inscriptions are now known, including three slightly earlier Ptolemaic decrees: the Decree of Alexandria in 243 BC, the Decree of Canopus in 238 BC, and the Memphis decree of Ptolemy IV, c. 218 BC. The Rosetta Stone is no longer unique, but it was the essential key to modern understanding of ancient Egyptian literature and civilisation. The term Rosetta Stone is now used to refer to the essential clue to a new field of knowledge.

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

External links:

- Rosetta Stone @ Wikipedia