Elisha Gray (nonfiction): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

Because of Samuel White's opposition to Gray working on the telephone, Gray did not tell anybody about his invention for transmitting voice sounds until February 11, 1876 (Friday). Gray requested that his patent lawyer William D. Baldwin prepare a "caveat" for filing at the US Patent Office. A caveat was like a provisional patent application with drawings and description but without a request for examination. | Because of Samuel White's opposition to Gray working on the telephone, Gray did not tell anybody about his invention for transmitting voice sounds until February 11, 1876 (Friday). Gray requested that his patent lawyer William D. Baldwin prepare a "caveat" for filing at the US Patent Office. A caveat was like a provisional patent application with drawings and description but without a request for examination. | ||

On Monday morning February 14, 1876, Gray signed and had notarized the caveat that described a telephone that used a liquid transmitter. Baldwin then submitted the caveat to the US Patent Office. That same morning a lawyer for Alexander Graham Bell submitted Bell's patent application. Which application arrived first is hotly disputed; Gray believed that his caveat arrived a few hours before Bell's application. Some recent authors have argued that Gray should be considered the true inventor of the telephone because Alexander Graham Bell allegedly stole the idea of the liquid transmitter from him, although Bell had been using liquid transmitters in his telephone experiments for more than two years previously. Bell's telephone patent was upheld in numerous court decisions. | On Monday morning February 14, 1876, Gray signed and had notarized the caveat that described a telephone that used a liquid transmitter. Baldwin then submitted the caveat to the US Patent Office. That same morning a lawyer for [[Alexander Graham Bell (nonfiction)|Alexander Graham Bell]] submitted Bell's patent application. Which application arrived first is hotly disputed; Gray believed that his caveat arrived a few hours before Bell's application. Some recent authors have argued that Gray should be considered the true inventor of the telephone because Alexander Graham Bell allegedly stole the idea of the liquid transmitter from him, although Bell had been using liquid transmitters in his telephone experiments for more than two years previously. Bell's telephone patent was upheld in numerous court decisions. | ||

In 1887 Gray invented the telautograph, a device that could remotely transmit handwriting through telegraph systems. Gray was granted several patents for these pioneer fax machines, and the Gray National Telautograph Company was chartered in 1888 and continued in business as The Telautograph Corporation for many years; after a series of mergers it was finally absorbed by Xerox in the 1990s. Gray's telautograph machines were used by banks for signing documents at a distance and by the military for sending written commands during gun tests when the deafening noise from the guns made spoken orders on the telephone impractical | In 1887 Gray invented the telautograph, a device that could remotely transmit handwriting through telegraph systems. Gray was granted several patents for these pioneer fax machines, and the Gray National Telautograph Company was chartered in 1888 and continued in business as The Telautograph Corporation for many years; after a series of mergers it was finally absorbed by Xerox in the 1990s. Gray's telautograph machines were used by banks for signing documents at a distance and by the military for sending written commands during gun tests when the deafening noise from the guns made spoken orders on the telephone impractical. | ||

Gray displayed his telautograph invention in 1893 at the 1893 Columbian Exposition and sold his share in the telautograph shortly after that. Gray was also chairman of the International Congress of Electricians at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. | Gray displayed his telautograph invention in 1893 at the 1893 Columbian Exposition and sold his share in the telautograph shortly after that. Gray was also chairman of the International Congress of Electricians at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. | ||

Gray conceived of a primitive closed-circuit television system that he called the "telephote". Pictures would be focused on an array of selenium cells and signals from the selenium cells would be transmitted to a distant station on separate wires. At the receiving end each wire would open or close a shutter to recreate the image. | Gray conceived of a primitive closed-circuit television system that he called the "telephote". Pictures would be focused on an array of selenium cells and signals from the selenium cells would be transmitted to a distant station on separate wires. At the receiving end each wire would open or close a shutter to recreate the image. | ||

| Line 39: | Line 40: | ||

* [[Telephone (nonfiction)]] | * [[Telephone (nonfiction)]] | ||

External links | == External links == | ||

* [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisha_Gray Elisha Gray] @ Wikipedia | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisha_Gray Elisha Gray] @ Wikipedia | ||

Latest revision as of 11:49, 21 January 2022

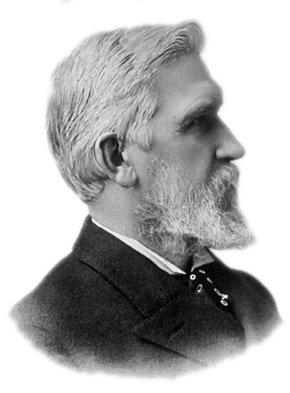

Elisha Gray (August 2, 1835 – January 21, 1901) was an American electrical engineer who did pioneering work in electrical information technologies, including the telephone.

Born into a Quaker family in Barnesville, Ohio, Gray was brought up on a farm. He spent several years at Oberlin College where he experimented with electrical devices. Although Gray did not graduate, he taught electricity and science there and built laboratory equipment for its science departments.

In 1862 while at Oberlin, Gray met and married Delia Minerva Shepard.

In 1865 Gray invented a self-adjusting telegraph relay that automatically adapted to varying insulation of the telegraph line. In 1867 Gray received a patent for the invention, the first of more than seventy.

In 1869, Elisha Gray and his partner Enos M. Barton founded Gray & Barton Co. in Cleveland, Ohio to supply telegraph equipment to the giant Western Union Telegraph Company. The electrical distribution business was later spun off and organized into a separate company, Graybar Electric Company, Inc. Barton was employed by Western Union to examine and test new products.

In 1870, Gray developed a needle annunciator for hotels and another for elevators. He also developed a microphone printer which had a typewriter keyboard and printed messages on paper tape. In 1872 Western Union, then financed by the Vanderbilts and J. P. Morgan, bought one-third of Gray and Barton Co. and changed the name to Western Electric Manufacturing Company of Chicago. Gray continued to invent for Western Electric.

In 1874, Gray retired to do independent research and development. Gray applied for a patent on a harmonic telegraph which consisted of multi-tone transmitters, that controlled each tone with a separate telegraph key. Gray gave several private demonstrations of this invention in New York and Washington, D.C. in May and June 1874.

Gray was a charter member of the Presbyterian Church in Highland Park, Illinois. At the church, on December 29, 1874, Gray gave the first public demonstration of his invention for transmitting musical tones and transmitted "familiar melodies through telegraph wire" according to a newspaper announcement.

Because of Samuel White's opposition to Gray working on the telephone, Gray did not tell anybody about his invention for transmitting voice sounds until February 11, 1876 (Friday). Gray requested that his patent lawyer William D. Baldwin prepare a "caveat" for filing at the US Patent Office. A caveat was like a provisional patent application with drawings and description but without a request for examination.

On Monday morning February 14, 1876, Gray signed and had notarized the caveat that described a telephone that used a liquid transmitter. Baldwin then submitted the caveat to the US Patent Office. That same morning a lawyer for Alexander Graham Bell submitted Bell's patent application. Which application arrived first is hotly disputed; Gray believed that his caveat arrived a few hours before Bell's application. Some recent authors have argued that Gray should be considered the true inventor of the telephone because Alexander Graham Bell allegedly stole the idea of the liquid transmitter from him, although Bell had been using liquid transmitters in his telephone experiments for more than two years previously. Bell's telephone patent was upheld in numerous court decisions.

In 1887 Gray invented the telautograph, a device that could remotely transmit handwriting through telegraph systems. Gray was granted several patents for these pioneer fax machines, and the Gray National Telautograph Company was chartered in 1888 and continued in business as The Telautograph Corporation for many years; after a series of mergers it was finally absorbed by Xerox in the 1990s. Gray's telautograph machines were used by banks for signing documents at a distance and by the military for sending written commands during gun tests when the deafening noise from the guns made spoken orders on the telephone impractical.

Gray displayed his telautograph invention in 1893 at the 1893 Columbian Exposition and sold his share in the telautograph shortly after that. Gray was also chairman of the International Congress of Electricians at the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Gray conceived of a primitive closed-circuit television system that he called the "telephote". Pictures would be focused on an array of selenium cells and signals from the selenium cells would be transmitted to a distant station on separate wires. At the receiving end each wire would open or close a shutter to recreate the image.

In 1899 Gray moved to Boston where he continued inventing. One of his projects was to develop an underwater signaling device to transmit messages to ships. One such signaling device was tested on December 31, 1900. Three weeks later, on January 21, 1901, Gray died from a heart attack in Newtonville, Massachusetts.

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

External links

- Elisha Gray @ Wikipedia