Paolo Sarpi (nonfiction): Difference between revisions

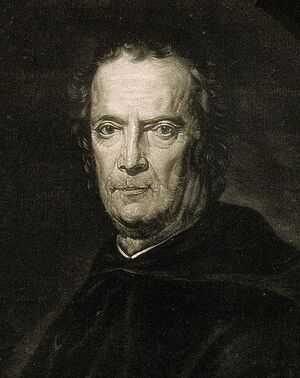

(Created page with "thumb|Paolo Sarpi (1777).'''Paolo Sarpi''' (14 August 1552 – 15 January 1623) was an Italian historian, prelate, scientist, canon lawyer, and states...") |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

His writings, frankly polemical and highly critical of the Catholic Church and its Scholastic tradition, "inspired both Hobbes and Gibbon in their own historical debunkings of priestcraft." Sarpi's major work, the History of the Council of Trent (1619), was published in London in 1619; other works: a ''History of Ecclesiastical Benefices, History of the Interdict and his Supplement to the History of the Uskoks'', appeared posthumously. Organized around single topics, they are early examples of the genre of the historical monograph. | His writings, frankly polemical and highly critical of the Catholic Church and its Scholastic tradition, "inspired both Hobbes and Gibbon in their own historical debunkings of priestcraft." Sarpi's major work, the History of the Council of Trent (1619), was published in London in 1619; other works: a ''History of Ecclesiastical Benefices, History of the Interdict and his Supplement to the History of the Uskoks'', appeared posthumously. Organized around single topics, they are early examples of the genre of the historical monograph. | ||

As a defender of the liberties of Republican Venice and proponent of the separation of Church and state, Sarpi attained fame as a hero of republicanism and free thought and possible crypto Protestant. His last words, "Esto perpetua" ("may she [i.e., the republic] live forever"), were recalled by John Adams in 1820 in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, when Adams "wished 'as devoutly as Father Paul for the preservation of our vast American empire and our free institutions', as Sarpi had wished for the preservation of Venice and its institutions | As a defender of the liberties of Republican Venice and proponent of the separation of Church and state, Sarpi attained fame as a hero of republicanism and free thought and possible crypto Protestant. His last words, "Esto perpetua" ("may she [i.e., the republic] live forever"), were recalled by John Adams in 1820 in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, when Adams "wished 'as devoutly as Father Paul for the preservation of our vast American empire and our free institutions', as Sarpi had wished for the preservation of Venice and its institutions." | ||

Sarpi was also an experimental scientist, a proponent of the [[Nicolaus Copernicus (nonfiction)|Copernican system]], a friend and patron of [[Galileo Galilei (nonfiction)|Galileo Galilei]], and a keen follower of the latest research on anatomy, astronomy, and ballistics at the University of Padua. His extensive network of correspondents included Francis Bacon and William Harvey. | Sarpi was also an experimental scientist, a proponent of the [[Nicolaus Copernicus (nonfiction)|Copernican system]], a friend and patron of [[Galileo Galilei (nonfiction)|Galileo Galilei]], and a keen follower of the latest research on anatomy, astronomy, and ballistics at the University of Padua. His extensive network of correspondents included Francis Bacon and William Harvey. | ||

Sarpi believed that government institutions should rescind their censorship of Avvisi - the newsletters which started to be common in his time - and instead of censorship publish their own version so as to combat enemy publication. Acting himself in that spirit, Sarpi published several pamphlets in defense of Venice's rights over the Adriatic. As such, Sarpi could be considered as an early advocate of the Freedom of the Press, though the concept did not yet exist in his lifetime. | Sarpi believed that government institutions should rescind their censorship of Avvisi - the newsletters which started to be common in his time - and instead of censorship publish their own version so as to combat enemy publication. Acting himself in that spirit, Sarpi published several pamphlets in defense of Venice's rights over the Adriatic. As such, Sarpi could be considered as an early advocate of the Freedom of the Press, though the concept did not yet exist in his lifetime. | ||

On 5 October 1607 Sarpi was attacked by assassins and left for dead with fifteen stiletto thrusts, but he recovered. His attackers found both refuge and a welcome reception in the papal territories (described by a contemporary as a "triumphal march"), and papal enthusiasm for the assassins only cooled after learning that Brother Sarpi was not dead after all. The leader of the assassins, Poma, declared that he had attempted the murder for religious reasons. Sarpi himself, when his surgeon commented on the ragged and inartistic character of the wounds, quipped dryly, "Agnosco stylum Curiae Romanae" ("I recognize the style of the Roman Curia"). Sarpi's would-be assassins settled in Rome, and were eventually granted a pension by the viceroy of Naples, Pedro Téllez-Girón, 3rd Duke of Osuna. | |||

The remainder of Sarpi's life was spent peacefully in his cloister, though plots against him continued to be formed, and he occasionally spoke of taking refuge in England. When not engaged in preparing state papers, he devoted himself to scientific studies, and composed several works. He served the state to the last. The day before his death, he had dictated three replies to questions on affairs of the Venetian Republic, and his last words were "Esto perpetua," or "may she endure forever. | |||

== In the News == | == In the News == | ||

Latest revision as of 18:53, 6 August 2017

Paolo Sarpi (14 August 1552 – 15 January 1623) was an Italian historian, prelate, scientist, canon lawyer, and statesman active on behalf of the Venetian Republic during the period of its successful defiance of the papal interdict (1605–1607) and its war (1615–1617) with Austria over the Uskok pirates.

His writings, frankly polemical and highly critical of the Catholic Church and its Scholastic tradition, "inspired both Hobbes and Gibbon in their own historical debunkings of priestcraft." Sarpi's major work, the History of the Council of Trent (1619), was published in London in 1619; other works: a History of Ecclesiastical Benefices, History of the Interdict and his Supplement to the History of the Uskoks, appeared posthumously. Organized around single topics, they are early examples of the genre of the historical monograph.

As a defender of the liberties of Republican Venice and proponent of the separation of Church and state, Sarpi attained fame as a hero of republicanism and free thought and possible crypto Protestant. His last words, "Esto perpetua" ("may she [i.e., the republic] live forever"), were recalled by John Adams in 1820 in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, when Adams "wished 'as devoutly as Father Paul for the preservation of our vast American empire and our free institutions', as Sarpi had wished for the preservation of Venice and its institutions."

Sarpi was also an experimental scientist, a proponent of the Copernican system, a friend and patron of Galileo Galilei, and a keen follower of the latest research on anatomy, astronomy, and ballistics at the University of Padua. His extensive network of correspondents included Francis Bacon and William Harvey.

Sarpi believed that government institutions should rescind their censorship of Avvisi - the newsletters which started to be common in his time - and instead of censorship publish their own version so as to combat enemy publication. Acting himself in that spirit, Sarpi published several pamphlets in defense of Venice's rights over the Adriatic. As such, Sarpi could be considered as an early advocate of the Freedom of the Press, though the concept did not yet exist in his lifetime.

On 5 October 1607 Sarpi was attacked by assassins and left for dead with fifteen stiletto thrusts, but he recovered. His attackers found both refuge and a welcome reception in the papal territories (described by a contemporary as a "triumphal march"), and papal enthusiasm for the assassins only cooled after learning that Brother Sarpi was not dead after all. The leader of the assassins, Poma, declared that he had attempted the murder for religious reasons. Sarpi himself, when his surgeon commented on the ragged and inartistic character of the wounds, quipped dryly, "Agnosco stylum Curiae Romanae" ("I recognize the style of the Roman Curia"). Sarpi's would-be assassins settled in Rome, and were eventually granted a pension by the viceroy of Naples, Pedro Téllez-Girón, 3rd Duke of Osuna.

The remainder of Sarpi's life was spent peacefully in his cloister, though plots against him continued to be formed, and he occasionally spoke of taking refuge in England. When not engaged in preparing state papers, he devoted himself to scientific studies, and composed several works. He served the state to the last. The day before his death, he had dictated three replies to questions on affairs of the Venetian Republic, and his last words were "Esto perpetua," or "may she endure forever.

In the News

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

External links:

- Paolo Sarpi @ Wikipedia

Attribution: